5 Lessons from Analyzing +50 Quality Businesses

A reflective roundup on moats, margins, founders, TAM, and the realities of long-term compounding

Every year, I end up analyzing dozens of public companies.

Some I own, some I’m researching, and some I revisit to check if the narrative has changed.

This year, I went deeper than usual, studying more than 50 quality growth companies across software, semiconductors, fintech, pharma, consumer goods, and emerging markets.

A few of these companies are thriving, a few are stagnating, and a few are heading towards a structural decline.

After spending hundreds of hours reading reports and watching talks and presentations on these quality businesses, four lessons stood out as the most important.

These lessons have shifted my thinking on moats, founders, valuations, TAMs, and how compounders work.

These are the lessons worth carrying into 2026.

1. Moats Don’t Collapse Overnight: They Erode Slowly From Within

The biggest surprise for me this year:

Most moats don’t deteriorate because of stronger competition.

They deteriorate because the market leader stops defending them.

Pattern #1: Complacency follows years of high returns

When a company compounds at 25–30% for a decade, leadership often becomes overly confident. They become defensive; instead of continuing at the same tempo, they underinvest, focus on protecting the core business instead of expanding it, and assume that the competitive landscape will remain the same.

This is exactly how PayPal lost market share and how Starbucks lost momentum before its reset.

Pattern #2: Culture drift destroys more moats than competition ever will

Culture compounds and is not gone in an instant; it takes years for it to erode.

However, a weak CEO can accelerate this decay with the right activities.

Over the long term, culture becomes one of the most important factors for compounding.

In 2024, the technology company I work for made a large merger with another “complementary” business. The result 2 years later?

The original culture of innovation and entrepreneurship is in shambles.

Multiple levels of middle managers make decision-making processes long and demanding—creating a slow-moving organization.

The new management group lacks vision and direction; the result is that many of the greatest employees leave for more exciting opportunities.

The competitive advantage we have in the business is shrinking by the day due to our lack of execution.

Pattern #3: Failure to adapt to platform shifts

Market leaders are not disrupted by technology, but by their inability to adapt to new technology.

We see large businesses fail to use cloud, mobile, and AI to improve their existing business.

On the other hand, leaders like Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon are adapting to the new technology and leveraging their existing business to get more out of it than any startup ever could.

Take Alphabet as an example. Incredible distribution with billions of active users across platforms. The implementation of their AI model, Gemini, now has over 650 million monthly users, and the “AI mode” in Search is reported to have +75 million daily users. A prime example of how an incumbent can adapt to new technology to unlock massive upside potential.

Fear not new technology, but fear an incumbent’s ability to adapt to it.

2. Founder-Led ≠ Founder-Quality

Founder-led companies outperform in aggregate, but the distribution is extremely uneven.

This year, I saw a clear split:

The elite founders

Bezos, Mark Leonard, Jensen Huang, Zuckerberg, Galperin.

These founders are customer-obsessed, paranoid, disciplined, and rational capital allocators.

The mediocre founders

Far more common.

They:

Overestimate their abilities

Chase side projects/distractions

Refuse to delegate

Cling to power

Ignore competitive threats

Run vanity initiatives

Operate emotionally, not data-driven

What actually matters isn’t “founder-led”

It is:

The intelligence, self-awareness, discipline, incentive, and the ability to set the business above the founder’s own ego.

A prime example of a poor founder-led business is WeWork and Adam Neumann.

Neumann used the company as his personal piggy bank, had incredibly poor capital allocation skills and discipline, and built a real-estate company disguised as a “tech” company to justify its insane valuations.

The founder was charismatic, but the lack of business intelligence and self-awareness was WoWork’s detriment.

3. Margins Matter Less Than Investors Think

Margins are one of the most misunderstood metrics in investing.

The understanding of margins requires a deep understanding of the context and growth phase a business is in.

Here’s what surprised me this year:

High margins ≠ High quality

In many cases, very high margins signal the end of aggressive reinvestment.

They reflect maturity, not future runaway compounding.

For mature, predictable, and defensive businesses, this is a good thing. But if you want a compounder that can grow above average for the long term, it is also worth looking at low-margin businesses.

Low margins ≠ Low quality

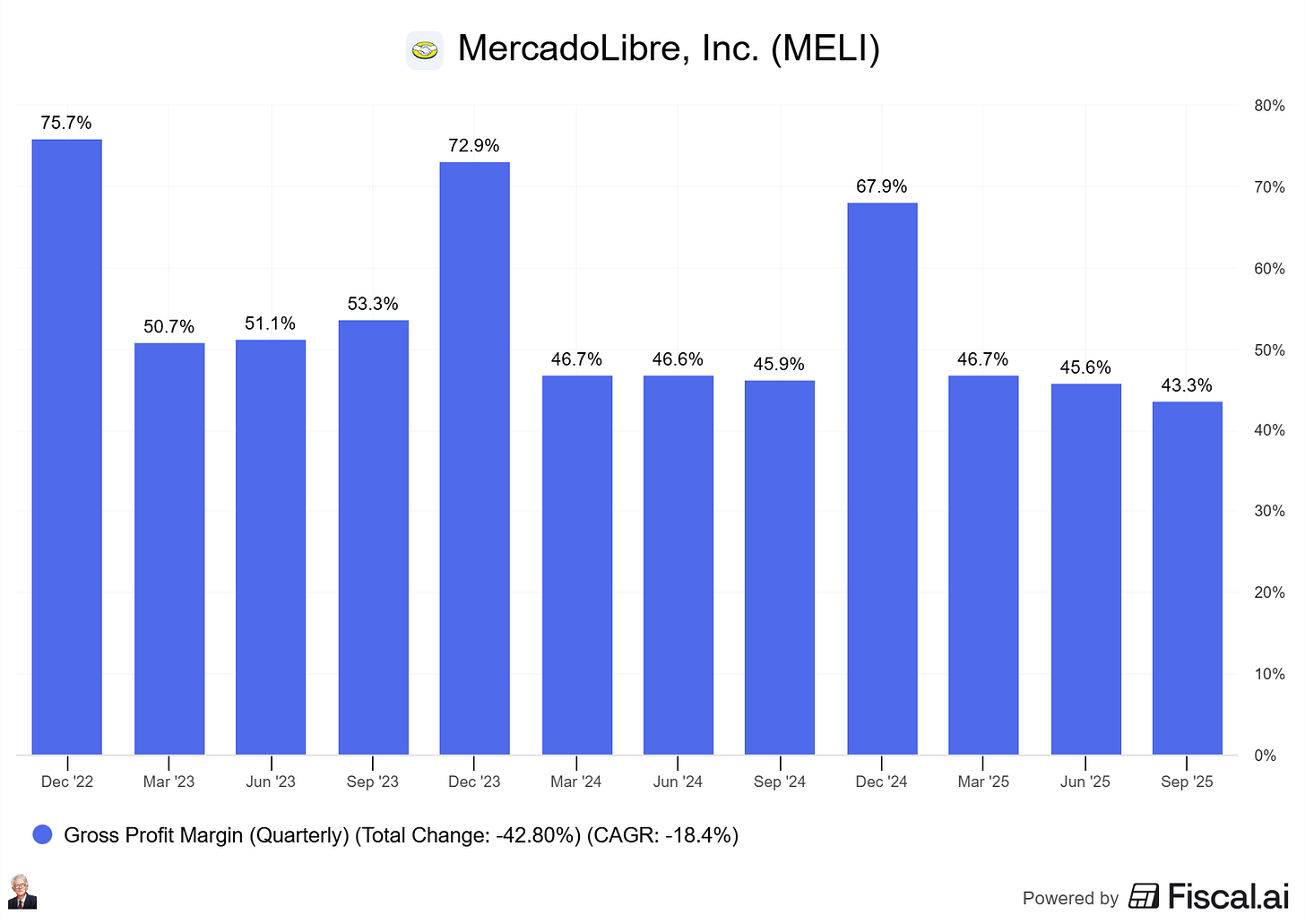

Amazon, TSMC, ASML, Tesla, MercadoLibre, and Shopify all had low margins during the years their moats were being built.

Margins were low by choice because reinvestment was high.

We see compounders like Mercadolibre deliberately lowering their margins to gain market share and top-line growth. This is a compounding strategy and not necessarily a negative.

What actually matters:

Long-term gross margins (Higher than industry average signals competitive advantage)

Incremental ROIC

Pricing power

Switching costs

Customer Life Time Value

Scalability

Reinvestment runway (At high incremental ROIC)

Margins are not the moat, but a result of the moat.

4. Total Addressable Market (TAM) Is Overrated

This year made one thing clear:

Investors overweight TAM and underweight competitive structure.

The best companies of the last 30 years often started in tiny, ignored markets:

Constellation Software → obscure micro-verticals

TSMC → niche contract manufacturing

Hermès → ultra-narrow luxury segment

Cadence/Synopsys → tiny EDA niche

MercadoLibre → early online auctions in Latin America

None of these started in billion-dollar TAMs.

They built strong businesses in their niches first and tapped into large TAMs later.

Meanwhile, large TAM narratives often collapse under their own weight:

Space

Fintech

Web3

EVs

Digital health

“Super app” models

Large TAMs attract capital, hype, copycats, regulators, and commoditization.

Just because there is a large TAM doesn’t mean that a business is positioned to take any meaningful part of that market.

Large TAMs are a poor predictor of business performance, and it can be a distraction for investors to focus too much on this.

5. The True Equation of Long-Term Investing

After studying 50+ companies, I keep returning to one simple truth:

The market tends to overvalue ultra-high growth.

And it undervalues the durability of growth and business.

A company with modest growth but extremely durable economics outperforms a fast grower with a fragile foundation.

We’ve seen some examples in recent times:

Duolingo's stock price crashes after a narrative shift to stagnating daily active users, and AI-driven competitors emerge:

The best long-term performers share five traits:

Excellent management team that adapts to trends and technology

Capital light business model

Sustainable competitive advantage (And business resiliency)

Source of organic growth and demand for its services

Lower than average sensitivity to market cyclicality

The more I study great businesses, the more I believe the entire game of long-term investing can be summarized as:

Look for companies that dominate a growing niche, defend it with a durable competitive advantage, and are led by managers who both care deeply and allocate capital with discipline. Pay a price that doesn’t require perfection to get good returns.

It’s a simple yet effective strategy in the increasingly noisy markets.

Conclusion

Studying 50+ companies this year didn’t just sharpen my filter, it also rewired how I think about quality.

The four most important takeaways:

1) Businesses that don’t adapt see their moats erode quickly.

2) Founder-led is not enough, founder-quality is what matters.

3) Margins are the output, not the input. Context matters.

4) TAM is overrated; durability is underrated.

Long-term quality investing is an act of discipline.

Most people chase alpha by investing in momentum stocks.

I don’t condemn using momentum as a tool, but most investors will invest in a stock only because the stock price is increasing, without understanding the long-term fundamentals.

This is the “get poor quick” scheme for most investors.

That’s it for today. Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Ready to take the next step? Here’s how I can help you grow your investing journey:

Go Premium — Unlock exclusive content and follow our market-beating Quality Growth portfolio. Learn more here.

Essentials of Quality Growth — Join over 300 investors who have built winning portfolios with this step-by-step guide to identifying top-quality compounders. Get the guide.

Free Valuation Cheat Sheet — Discover a simple, reliable way to value businesses and set your margin of safety. Download now.

Free Guide: How to Identify a Compounder — Learn the key traits of companies worth holding for the long term. Access it here.

Free Guide: How to Analyze Financial Statements — Master reading balance sheets, income statements, and cash flows. Start learning.

Get Featured — Promote yourself to over 24,000 active stock market investors with a 42% open rate. Reach out: investinassets20@gmail.com

This article comes at the perfect time, thank you for articulatng so clearly how organizational complacency sistematically erodes even the strongest competitive advantages over time.

Agree large TAM is not a predictor of good performance but common sense would imply that small TAM should be a predictor of growth stock underperformance, that is frequently overlooked when the “can this company grow into its multiple?” question is asked imo